In May 2021, the operator of the US’s largest fuel pipeline paid $4.4m to a group of hackers who broke into the company’s computer systems. The owners of the Colonial Pipeline, which carries fuel to south-eastern parts of the US, made the payment to return operations after a ransomware cyberattack, the largest ever attack on US oil infrastructure.

More than 9500 filling stations were out of fuel, causing panic-buying and severe fuel shortages. What followed was the intervention of the federal government, the help of engineers to recover systems and a ransomware negotiation with the hackers known as Darkside.

It is now two years since the Colonial Pipeline incident. The mayhem it caused became a point of departure to address the elephant in the room – cybersecurity.

Moving cybersecurity thinking beyond the firewall

Cyberattacks on oil and gas infrastructure promise maximum disruption and massive monetary negotiations. As offshore oil and gas infrastructure increasingly becomes reliant on remotely connected operational technology, it also makes facilities vulnerable to cybersecurity threats. Offshore operations are multifaceted, and legacy software like antiviruses or firewalls are not enough to protect critical national infrastructure.

“While such approaches are still employed, they fail to identify inherent vulnerabilities within the operational technology (OT) systems, are unable to detect suspicious or potentially dangerous operations such as unscheduled controller updates, or highlight behavioural anomalies associated with cyber-attacks, whether initiated externally or internally,” says Paul Evans, UK sales engineer at Nozomi Networks.

Reports indicate that more than 1600 offshore facilities in the US rely on remote monitoring technology. Any cybersecurity attack on such firms can cause major economic disruptions, impact supplies to the market and affect prices. Moreover, any tampering with technology that is monitored or controlled by internet of things (IoT) devices can result in spills, fires and cause marine or environmental damage.

Addressing these blind-spots in the oil and gas industry means cybersecurity standards and benchmarks being adopted by, or enforced upon, operators.

”Offshore is a difficult environment in which to consider cybersecurity”

The foremost concern for adopting cybersecurity measures is a predictable one – the cost of upgrading infrastructure.

Oil and gas companies are dependent on assets that span across multiple generations of technologies. While some may be compatible with the evolved security threats, others may need a digital upgrade or replacement.

Tony Burton, the managing director of cybersecurity company Thales, says: “Like many other sectors that are heavily dependent on OT, offshore oil and gas assets are expensive to commission, maintain and decommission, and this makes for a difficult environment in which to consider cybersecurity investment cases.”

Yet, companies are now posturing their infrastructure to identify and prevent criminal activity. According to Offshore Technology Focus’s parent company GlobalData, the Norwegian multinational energy company Equinor invested $554m in safety and automation deals to build its cybersecurity defence. Austrian firm OMV introduced training for its 27,000 employees and implemented multifactor authentication across its organisation’s systems. Companies like ExxonMobil, Repsol, and ONGC have all jumped on the cybersecurity bandwagon.

But what are the usual weak links in the offshore infrastructure that allow cybercrimes to take place? It is perhaps worth remembering that, in the case of Colonial, a single password compromised with an out of date VPN allowed the hackers to gain access.

The vulnerable and weak links in oil and gas companies

To effectively prioritize cyber investments in the offshore industry, it is crucial to frame the cyber issue in terms of business risks, threats to human and environmental safety, and the cost of compromising critical national infrastructure.

The severity of an attack also encompasses other indirect costs, including legal claims, reputational damage and intellectual property theft.

Different stages of the value chain have distinct cyber risk profiles. Exploration has the lowest vulnerability and severity of risk, since it involves only seismic and geological data. The loss of this presents a low risk of disruption to business, however the company’s competitive field data can be attacked. Attacks in the exploratory stage can go unnoticed for the lack of immediate bearings on costs or operations.

For instance, the Night Dragon attacks of 2006 procured executive, confidential information of oil and gas field bids and operations. More than 71 companies, including ones in the energy sector, were compromised for several years until the attacks came to light in 2011.

The development drilling stage poses the highest risk, due to its infrastructural expanse, interconnected IoT and sensor-based systems and the potential for significant financial losses. In 2014, a cyber-attack caused an oil rig off the coast of Africa to tilt to one side. It shut down the production process for a week until engineers identified the breach and regained control.

Production and abandonment operations with legacy assets and limited monitoring tools, rank highest in cyber vulnerability.

Identifying weak links “is about the oil and gas industry becoming more resilient, and this is only achieved by understanding what you have, understanding the threat and risk position, and then working towards a set of actions that will bring those risks to a level that the organisation can tolerate,” says Burton.

The dual role of the dark web

The dark web is a part of the internet that isn’t indexed by search engines and this anonymising nature facilitates buying, selling and trading of companies’ credentials for illegal purposes such as ransomware and online extortion. On one hand, the dark web is the epicentre of compromised information and criminal activity. On the other, it presents as a resource for security cells to observe, identify and build threat resistance.

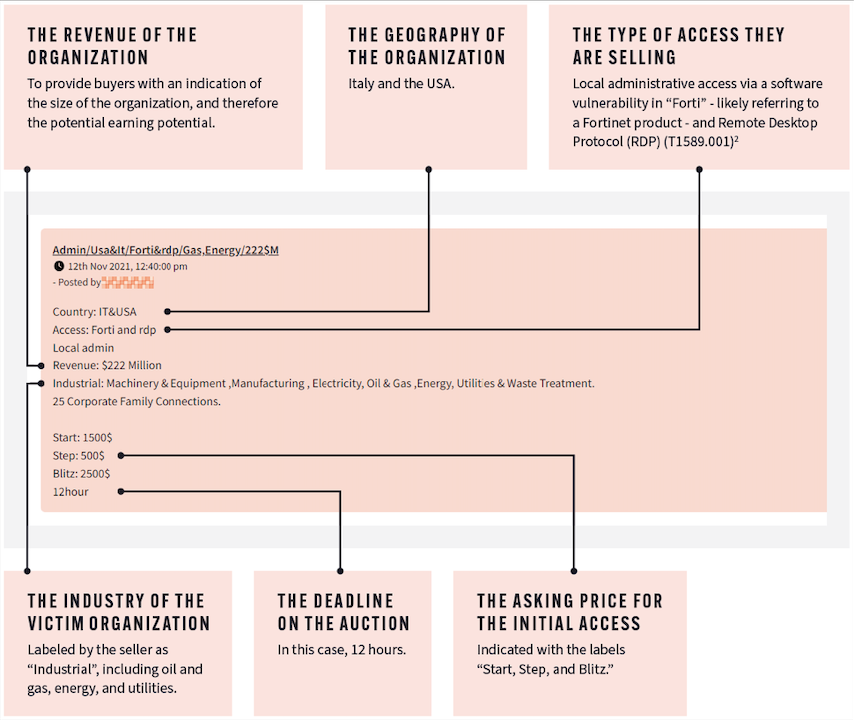

A 12-month research project by Searchlight Cyber, an organisation that provides dark web intelligence, observed how energy companies are targeted on the dark web. While energy companies may not have historically thought of themselves as targets, criminals are now leveraging the critical nature of assets managed by these companies to extort huge sums of money.

Monitoring the activity on the dark web can help companies identify paths of an attack, prepare defences and build threat models for future resistance. The report observes that the predominant activities against energy companies coming from the dark web are auctions for initial access to companies’ systems.

“With information on the revenue, location, and technology of the potential victim, security teams can identify if their clients fit the profile given at auction and take mitigative action. Even if they don’t fit the exact profile of the victim, they know this is a tactic being used against other energy companies that they should factor into their threat modelling,” says Jim Simpson, the director of threat intelligence at Searchlight Cyber and co-author of the report.

When asked about the most watertight approach to cybersecurity, he adds: “The best approach to security is to assume that everything is going to fail. If it is made by a person, it can be broken by a person. And what you want to do is get multiple security controls in place so that you can identify threats as they occur. You want to have preventative controls and then a layer of detective controls in case your preventative controls fail.”

Benchmarking cybersecurity standards

One way of securing critical infrastructure is to institute its security in law. As a response to the Colonial Pipeline hack, the US Congress passed the Strengthening American Cybersecurity Act that mandated reporting of cyber intrusions to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency within 72 hours, or 24 hours in case of ransom. As legislations lapse, oil and gas companies are now including security standards and corresponding cyber tooling conditions in contracts with their service providers.

The challenges to the energy industry are not unique, however the operational variables make it difficult to halt activity and modify underlying infrastructure. This can cause delays until a suitable maintenance window is available.

Further, the deployment of cybersecurity needs a significant shift in mindset. Vendors are often reluctant to use defensive measures “due to a perception that such tooling may impact system performance and hence effect their service-level agreemets, even when the same tooling has been deployed multiple times within their systems for other customers,” information security consultant Paul Evans explains.

“Cybersecurity benchmarks typically centre around [international standards guidelines] IEC62443, ‘Industrial Network and System Security’, which provides guidance for the implementation of cybersecurity protection through the consideration of people, process, and cybersecurity tooling. The successor to the European Network and Information Systems (NIS) directive, NIS2, which also includes references to IEC62443, now includes oil and gas within its remit, and unlike IEC62443 which is a guideline, NIS2 is now law across EU countries as of January 2023, with multi-million dollar fines for non-compliance.”

Assessment of cybersecurity standards goes beyond its centricity on oil and gas facilities, businesses and consumers. Two years on, the Colonial Pipeline hack stands as a reminder for organisations and governments that risk prevention has to pave way for resilience-building against cyberattacks.