Chatbots are one of the main real-world business implementations of artificial intelligence (AI) software today, with companies all over the world using them to reduce the need for expensive human interaction with customers. As such, chatbot tech may seem to be a very modern phenomenon, and its widespread use is indeed quite recent. But in fact, chatbots have been around for a very long time.

The oldest chatbot on record is ELIZA, created from 1964 to 1966 by Joseph Weizenbaum at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. ELIZA’s origins lay in the famous Turing Test, devised by British computing genius Alan Turing in 1950. The test can only be passed by a machine if it convinces human players that it is as flesh and blood as they are. The ‘imitation game’ inspired Weizenbaum to create the ELIZA program as a parody of psychotherapy, and to debunk the hype over human-machine conversation’s capabilities.

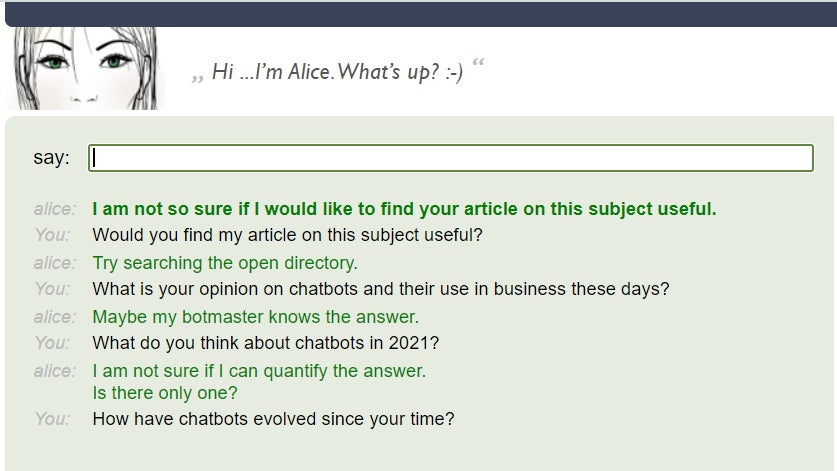

Under ELIZA’s hood was a program which recognised the input of clue words or phrases, with a corresponding output of pre-prepared responses. ELIZA later inspired AI researcher Richard Wallace to create ALICE (Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity) or Alice. The modern era’s oldest “living” chatbot, Alice has been online since its creation in 1995. Alice is recognisably a descendant of ELIZA, building on the design with more pre-configured templates of text and machine learning capabilities. Through an algorithm that analyses the user’s latest sentence by matching it against the patterns in its rules, Alice gives more complicated replies than Eliza, repeats less, and has more of a personality, professing a love for all things Star Trek and Star Wars.

Not that this necessarily makes for sparkling conversation: When Alice is stumped by a question, it throws back the question to you in the form of a question or awkwardly-phrased answer. Interacting with Alice today is a sobering reminder of why it took a while for chatbots to find their voice in mainstream internet.

Author in conversation with Alice

Author in conversation with Alice

Chatbots and AI in 2020

“When we first launched in 2016, chatbots were only known in niche circles, typically amongst technologists,” says Alex Debecker, founder and CMO of Ubisend, a chatbot platform with clients including NHS Digital and Unilever. “The wider public had no awareness of the technology or its potential. They were often considered gimmicky, and for a good reason: they mostly were.

“Early chatbot designs focused on flow conversations, taking users from point A to point B without much regard for what the user actually wants. They were also focused on friendly interactions; saying ‘hi’ to a chatbot and receive ‘hello’ back was considered a very important feature.”

Debecker tells Verdict that today’s chatbots do away with the small talk to be a lot more functional, designed mainly to serve and solve business-oriented purposes and challenges.

“While flows are still part of the general design,” he continues, “platforms like ours encourage building conversations with specific, data- and AI-driven transitions between steps.

“Today’s chatbot users want efficiency. They want accurate answers to their questions, instantly – not a friendly chat with a robot.”

The evolution of the chatbot came not from the academia that brought us Alice and ELIZA, but from the needs of big business and its customers. As AI technology is often embedded into larger systems, the market for artificial intelligence can be difficult to size; even harder is picking out the worth of chatbot tech from other AI sectors such as data parsing, computer vision and smart robotics.

That aside, GlobalData’s thematic research suggests that the market for AI platforms will reach $52bn in 2024, and a considerable amount of that revenue is driven by the popularity of virtual assistants like Alexa and Google Assistant.

Credit: Tada Images / Shutterstock

Credit: Tada Images / Shutterstock

AI rehab: Chatbots in business

While much of the discussion around AI conversational platforms is on the consumer application side, a growing number of companies across many industries are implementing virtual agents in areas ranging from customer service to human resources. Take banks; for many of their customers, the most visible use of AI in banking is friendly chatbots, of the sort which have helped fintech brands like Monzo and Revolut offer customer service without any customer-facing staff. But quality can vary when it comes to the basics, especially with bots offered by incumbent banks. Matt Deegan, business development director of London creative tech studio Rehab, highlights to Verdict issues such as banking bots’ tone of voice and poorly-timed responses.

“Sometimes you would be given a reference number on a letter but then you couldn’t use it when the chatbots asks for the number; it would even give the exact same question three times within seconds,” Deegan adds, citing such flaws as detrimental to the trust between customer and brand.

Rehab as a studio has been resolving these issues with award-baiting chatbots for the likes of Nike and HBO. Using cloud platforms like Twillio, Rehab decides on the right solution and input for the client. While the code may not be built from scratch, there is never a one-size-fits-all approach to business chatbots.

“It’s about getting the right personality, which all comes down to understanding the audience,” says James Penfold, Rehab’s head of strategy and experience design. “Chatbots have to align with the brand tone of voice, and how as a company it should be talking to people.

“Personality was huge on the Estée Lauder chatbot we worked on, Liv. A lot of it was understanding how makeup assistants talk to their customers and keeping the brand’s voice, even switching up the media involved.

“I think what worked very well with Liv is we didn’t only respond with text, but also videos and audio clips, with link outs to information and social media. This was more trying to mimic how you would chat with a friend on WhatsApp rather than how you’d expect a chatbot to respond to you.”

Failure of imitation

While it may seem counterproductive, Penfold says it was still important for Liv to talk in such a way that one could tell it was a robot, referring to transcripts showing how annoyed people can get with chatbots when under the impression they’re human beings. Call it the anti-Turing test, if you will.

“You’d always see people getting angry with it, asking ‘Why are you not responding?’ So I think it’s about being very honest with the user, and setting their expectations of what bots can and can’t do. Personality is important, but it’s not human, it’s an automated system. We’re giving it a sense of a personality without confusing or fooling anyone into thinking they’re talking to a human.

“It’s about how they handle failure. After all they’re only as smart as the input and training they have had from human teams. If they handle failure in a really ‘un-human’ way, it’s a very bad experience. But if they’re honest and say they don’t know this but are smart enough to point you in the right direction, then the customer isn’t going to be so frustrated that they resort to calling the call centre – which is what they’re trying to get you to stop doing!”

Brick-and-bots

Rehab places its work into the two camps of utility and entertainment. The latter includes a popular chatbot promoting, appropriately enough, AI sci-fi show Westworld. These are more about experience than anything else. For the utility kind, businesses might be using Rehab’s bots for cost savings on their call centres, or making sure customers complete online purchases. According to Debecker of Ubisend, cost saving has been the name of the game during the pandemic.

“Never before have businesses had to so drastically adapt to a sudden and catastrophic event,” he tells Verdict. “(But) businesses that had already taken the steps towards automation were able to adapt quickly. Amidst a pandemic, massive budget cuts and general uncertainty, Ubisend saw an increase in AI spending.

“The events of 2020 made it clear that deep automation and chatbots are no longer nice-to-have. They’re vital technologies that may separate resilient businesses from others.”

According to GlobalData analysts, chatbots from the likes of Ubisend and Rehab are helping businesses communicate with high volumes of customers daily and “provide a more personalised experience that drives growth, reduces costs, and improves retention and overall customer satisfaction.” Profiting highly from business’ love for chatbots are the likes of Microsoft and its Azure Bot Service; the tech titan bundles its Azure figures in with its Intelligent Cloud (IC) business segment, and its recent Q3 results showed IC revenue grew 23% year-on-year (YoY) to $15.12bn. Azure alone saw its revenue alone grow by 50% YoY.

Covid has clearly accelerated digital transition for many businesses. But while chatbots are native to our browsers and smartphone apps, Rehab thinks it might be too early to call a moratorium on brick-and-mortar shops – even if they may end up replacing some retail staff.

“Major brands and retailers are looking at how the chatbot on a website might actually be the first step in a customer journey which can then link to a physical experience,” Deegan says.

“You won’t need to go and interact directly with a store assistant as you can actually start to interact with a bot, whether that’s on your phone or triggered via something in the actual location,” Penfold explains. “Rehab has done a few trials of this with Nike using an in-store Pad you could come up to and run through, and which would highlight (relevant) sneakers on the wall.”

Rehab believes the next evolution of this would be customers walking into stores with their personal devices that they’ve done prior research on, triggering a virtual assistant to know that they’re in the shop. In turn the bot will highlight the products of interest to the customer.

“There’s still going to be a need for brick-and-mortar stores. They’re not going to vanish straight away,” Penfold believes.

Next-gen chatbots

Customer data shared between bot and store as they traverse physical and digital touchpoints echoes the way that today’s chatbots feed back data input by humans to companies to inform future product development. Information on questions asked which bots can’t answer can make for insightful market research; in other words, companies will be constantly learning from the machine learning they employ.

This doesn’t stop at text input, as Rehab’s vision of the future goes beyond brick-and-bot businesses. The studio expects computer vision (CV) to become another main driver behind AI uptake. Intelligent tech like CV allows a machine to accurately identify, classify and react to objects as if “seeing” them.

“Things will move away from two-way, text based-examples and into photo submissions which could be analysed,” Deegan envisions. “Think a photo of a broken product analysed by an algorithm to see if it’s their product and whether it’s broken, then triggering a returns policy in the chat experience.”

Computer vision could even help bots “see” how consumers are feeling through their front-facing camera; the audio equivalent known as computer audition could do the same with one’s voice, being able to “analyse the sentiment of how they’re talking to the bot and then being able to tailor the response to that sentiment,” says Penfold.

That said, don’t expect a descendant of ELIZA and Alice to pass the Turing test anytime soon. Building on their in-store bots for Nike, Penfold and Rehab think it’s more likely we’ll see a future ecosystem in which chatbots can co-exist and build connections for customers.

“There’s a big unknown around voice search,” he says. “If I ask Siri or Google for something on a mobile device, that would generally lead me to a brand website and then I’ll have to use the screen. That leaves a gap between the conversational experience on your phone and a brand’s conversation experience. This is a space where lots of people are looking to solve how you connect those two touch points without having to ask Google to do something every time.

“No one’s really got that killer app yet; there’s lots of very good chat experiences but I think the next big thing is when it actually all works together and it doesn’t matter if you’re using Facebook Messenger or your TV or an Alexa. When an app understands and connects it all, that’s when brands will see a real benefit because if connected with their website, then it’s connecting with everything that customers are doing with them as a brand.

“I think that’s what consumers are starting to expect. If anything, consumer expectations are higher than what the brands can actually deliver at the moment.”

By Verdict’s Giacomo Lee. Find the GlobalData Thematic Research: Artificial Intelligence (AI) report here.