When the US East Coast stopped receiving its oil in May 2021, events moved very quickly. Consumers began stockpiling fuel, causing a rush on the pumps. The federal government quickly became involved, and in the middle of this, engineers had to work out what went wrong.

While all well-informed oil and gas businesses know of the threat of cyberattack, few would have expected an intrusion as audacious, and even as obvious, as shutting down one of the country’s main arteries for fuel. One year on from the hack of the Colonial Pipeline company, and their oil transport mechanism of the same name, and expectations have changed.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe Colonial Pipeline hack and the unintended consequences

The Colonial pipeline moves fuel oil from Texan refineries to cities on the US’ East Coast, ending at Washington DC. Approximately 380 million litres of oil would flow through it on an average day, but on 7 May 2021, this stopped.

The hacking group DarkSide demanded payment to bring the pipeline back online, known as a ransomware attack. Their intrusion included billing and accounting software used by Colonial Pipeline, causing the company to shut systems down to prevent a spread.

While some quickly attributed the attack to foreign aggression, citing the well-known online disruption techniques used by Russia, the group itself denied this. While the group operates out of eastern Europe and Russia, a short statement from DarkSide said that the group considers itself “apolitical”.

“We do not participate in geopolitics,” a post said. “Our goal is to make money, and not creating [sic] problems for society. From today, we introduce moderation [sic] and check each company that our partners want to encrypt to avoid social consequences in the future.”

Federal agencies quickly became involved. The FBI, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Homeland Security all received notification of the hack.

The Department of Transportation issued an emergency declaration to create a virtual pipeline, using other transport routes to carry a fraction of what the pipeline would deliver. This allowed more drivers to make more deliveries with less mandated rest time, increasing risk by a difficult-to-measure amount. However, no incidents have been directly or widely attributed to these rule changes.

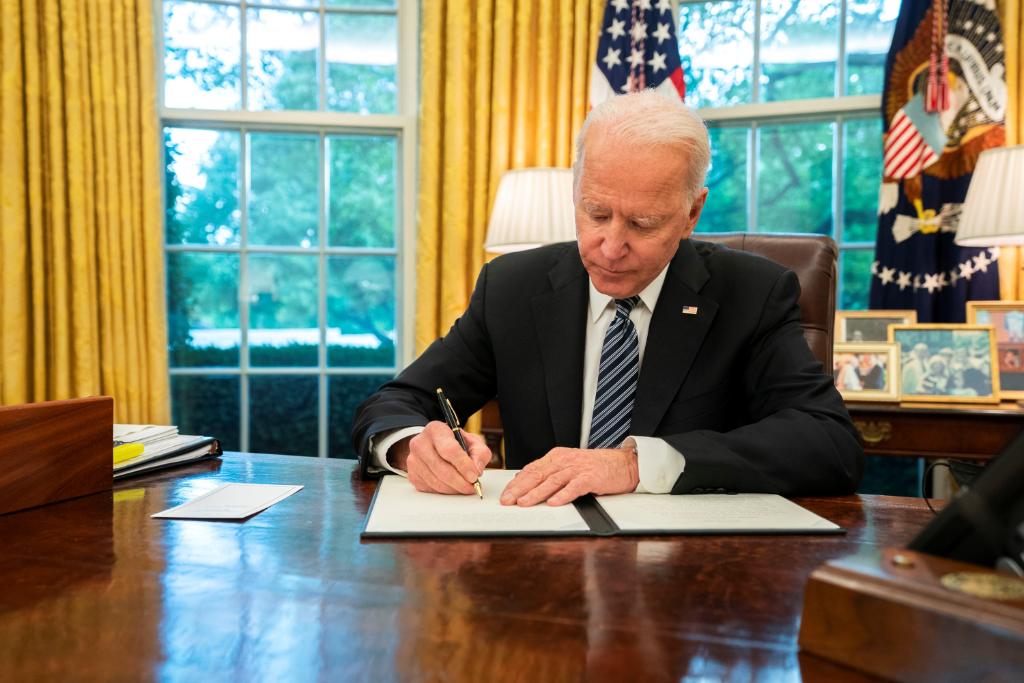

Within a week, US President Joe Biden signed an executive order to strengthen national cybersecurity. This would create a “standard playbook” of responses to wide-scale intrusions such as Colonial, and cause government agencies to increase security around their cloud services. It also set up a Cybersecurity Safety Review Board, which would effectively conduct inquiries after cyberattacks and give recommendations to prevent future incidents.

The same day, Colonial paid DarkSide approximately $5m in cryptocurrency for the key to decrypt their systems. Operations resumed on 12 May, and Biden told the public that, with a few hiccups, he expected “a region-to-region return to normalcy continuing into [the coming] week”. And that was the end of that.

Setting the stage for cybersecurity in the 2020s

The Colonial Pipeline intrusion ended relatively quickly, in an apparent victory for the hackers. However, it has had direct consequences for approaches to cybersecurity today, in ways that disadvantage hackers.

The Colonial incident put DarkSide squarely at the centre of the attentions of the US security services. The group shut down entirely on 17 May, collecting approximately $90m in bitcoin payments across its lifespan. Cybersecurity firms Intel 471 and FireEye said that the group blamed pressure from US Government agencies for its disbandment.

Then, in June, the US Department of Justice announced it had seized $2.3m in bitcoin back from DarkSide. The promised decentralisation of cryptocurrency relies on publicly accessible data on which payments go where, known as the blockchain. While this allows for some degree of anonymity, agencies with enough power and leverage can overcome this.

Department of Justice deputy attorney general Lisa Monaco said: “Following the money remains one of the most basic, yet powerful, tools we have. Ransom payments are the fuel that propels the digital extortion engine, and today’s announcement demonstrates that the US will use all available tools to make these attacks more costly and less profitable for criminal enterprises.

“Today’s announcements also demonstrate the value of early notification to law enforcement; we thank Colonial Pipeline for quickly notifying the FBI when they learned that they were targeted by DarkSide.”

New legislation to prevent another Colonial incident

In March 2022, US Congress passed the Strengthening American Cybersecurity Act (SACA). This response to the Colonial hack mandates that critical infrastructure operators report cyber intrusions to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency within 72 hours, or 24 hours if held to ransom. The EU and UK have also worked on similar acts since the hack, aiming to increase overall Western resilience to cyber threats.

However, the SACA is often superseded by rules imposed by the US’s Transportation Security Administration (TSA). Tighter regulations introduced directly following the hack have only just lapsed, with the TSA looking to relax rules for future incidents.

Stricter restrictions around reporting have been one of the most noticeable effects of these rules. Jori VanAntwerp, co-founder and CEO of network monitoring company SynSaber, told CSO Online: “One issue that comes up frequently in our conversations with critical infrastructure operators and asset owners is that they’re wary of additional reporting requirements. In the past, there has been little to nothing done with the information that they have provided to government entities.”

The previous, strengthened rules required companies to report ransomware cyber-intrusions to the government within 12 hours. The rule change on 29 May increased this to 24 hours, in line with the window required by the stock market regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Oil industry advocates have pushed for SEC window to increase to 72 hours, allowing three days to pass before shareholders must know of cyber intrusions. Lobbyists say that a 24-hour window does not allow for accurate reporting of intrusions.

“In the past, government agencies have done little with the information they get”

The TSA issued a second batch of rules in response to the Colonial hack in July 2021. These mandated that companies must use multi-factor authentication for accessing pipeline systems, and that password reset requirement must be strengthened. Given that many pipeline systems require on-site, in-person access, the cost of rolling this out to many smaller and widely-dispersed systems made companies sceptical of the stronger regulations.

Regulations will change again on 26 July. A spokesperson for the TSA said that the new regulations would proscribe less specific security measures to companies. Instead, the agency would move to a “performance-based model” that would require cybersecurity to advance as threats advance.

“The TSA is consulting with industry stakeholders and federal partners while modifying this security directive,” the spokesperson said.

Since the Colonial hack, companies have argued that the emergency rules have slowed their operations and could impede the delivery of oil and gas. Since the introduction of its second set of rules, the agency has received more than 380 requests from companies to differ from the rules it set.

Suzanne Lemieux, operations security director for trade organisation the American Petroleum Institute, told the Wall Street Journal: “We’re encouraged by the changes they’ve made. There were a lot of things that weren’t well thought out in the urgency of getting the rules out.”

Regardless of regulation, companies have also increased their spend on operational security. Darren van Booven, advisory practice lead for cybersecurity company Trustwave, told us that he has seen the number of operational technology security services double since the Colonial hack.

He continued: “This has mostly been driven by boards and directors, as a direct response to Colonial Pipeline. Organisation leaders are calling for security system audits and assessments, ransomware protection strategies, and detection and response capabilities for advanced threats, like cyber gangs.”