Forest-based carbon credits have had a rough couple of years. Numerous academic studies and media investigations have unearthed vastly inflated carbon savings and failed safeguards for forest communities amongst the world’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) projects, which boast a quarter of all carbon credits to date.

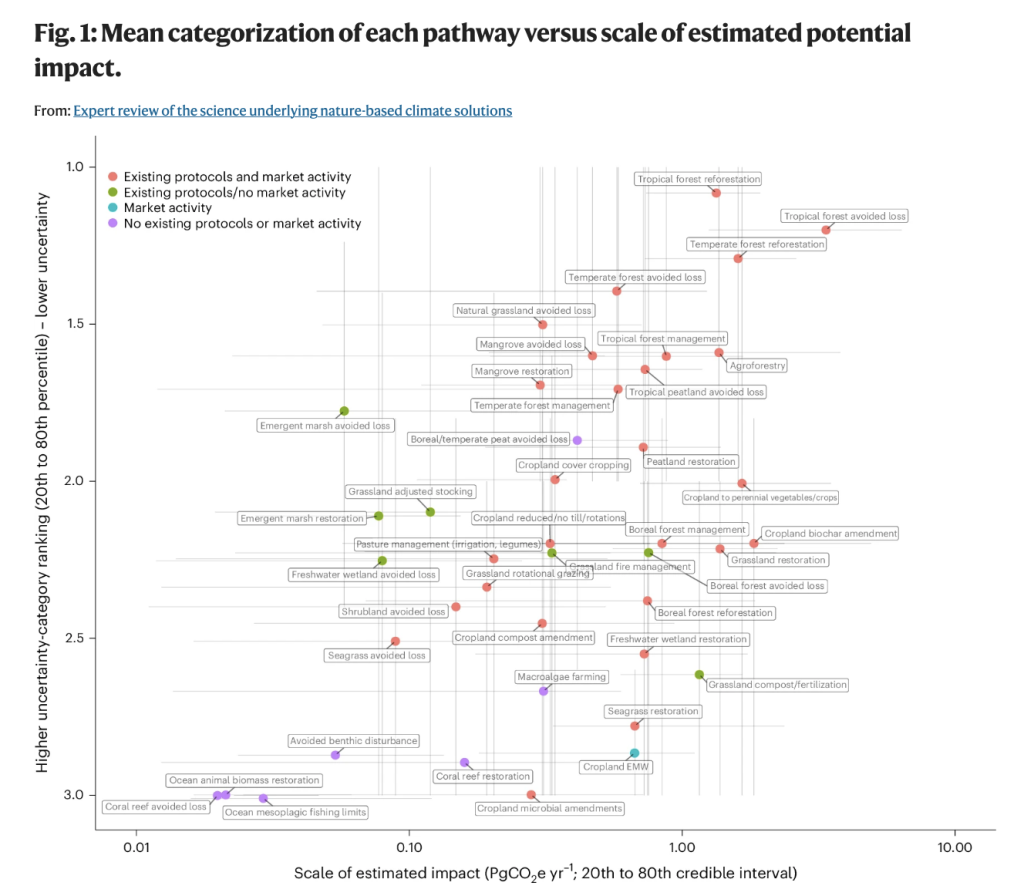

However, a new peer-reviewed Nature study by 27 researchers across 11 institutions including the Environmental Defence Fund (EDF), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the University of Columbia, has backed the industry’s scientific credentials: out of all the world’s nature-based climate solutions, the paper found that the four leading forest-based solutions have robust scientific foundations, while the others need urgent additional research before their role as a climate solution is understood. The study explicitly looked at the scientific basis of, and expert confidence in, the world’s known nature-based solutions (NBSs); rather than the implementation of individual projects, carbon crediting methodologies or co-benefits.

“In tropical forests, there have been complaints about whether those projects are doing what they purport to do – but that is an implementation challenge,” says Brian Buma, senior climate scientist at EDF and a co-author of the report. “For forests, we have a pretty good scientific basis and our methods just get better and more complementary. We have a lot of ways of measuring the carbon in forests and the associated fluxes. It is much harder to do in things like soil, for example.”

The study examined the scientific foundations of the climate warming mitigation potential of 43 NBSs, and then garnered independent expert judgment on their certainty. “Science is about bringing intelligence to action,” said co-author Peter Ellis, global director of natural climate solutions science at the TNC, in a press briefing. “That is exactly what we do in this paper: review the best available information to determine which nature-based climate solutions are ready for primetime.”

Four pathways – tropical forest conservation, temperate forest conservation, tropical forest reforestation and temperate forest reforestation – offer the greatest certainty in carbon mitigation potential, found the researchers. There is a small concern over how changes in precipitation may impact tropical forest carbon, according to Buma, but it was not sufficient to reduce the researcher’s overall confidence in the solutions.

“There has been some really great forest carbon projects recently, building on lessons learned and advances in remote sensing technology and best practices in stakeholder consultation,” says Mark Moroge, vice-president of natural climate solutions at EDF. “And we are now starting to see those come to market at scale – a new cohort of high-integrity, jurisdictional REDD+ programmes – with countries like Ghana and Costa Rica approaching issuances. There is some really amazing stuff out there – both from a climate and social impact perspective – but those stories don't appear to be getting out there in the media.”

However, the report found that other types of NBSs such as avoided seabed disturbance have scientific uncertainties at global scales and require further research. In some cases, the carbon markets are pushing the boundaries of these uncertainties: 77% of the NBSs with higher global uncertainties have protocols developed, and 62% already have market activity.

“Many companies are selling things that we can’t really quantify,” says Buma. “Coral reef solutions, for example, uniformly scored low in terms of their confidence to contribute as a climate solution – purely from a carbon perspective, rather than in respect to biodiversity, livelihoods or food security. I think there has been a lot of well meaning folks out there that have seen the carbon market as a way to finance a variety of environmental initiatives, regardless of their actual climate impact.”

However, there are also some NBSs that offer huge carbon mitigation potential that are still too nascent to have the science to back up their credentials. One such solution is enhanced rock weathering, a carbon removal technology that involves speeding up natural weathering and spreading the crushed rock over agricultural land in order to sequester more CO² in a shorter time frame. The space has seen significant investment in recent years, but there are still many unknowns about the environmental impacts of the process.

“It is a really exciting solution from both a carbon and crop productivity perspective, but we still haven’t answered some really key questions: what is the life cycle assessment of the whole process and can we actually do that? How much of the carbon is sequestered and how much goes back into the atmosphere? These need more research to properly answer,” says Buma.

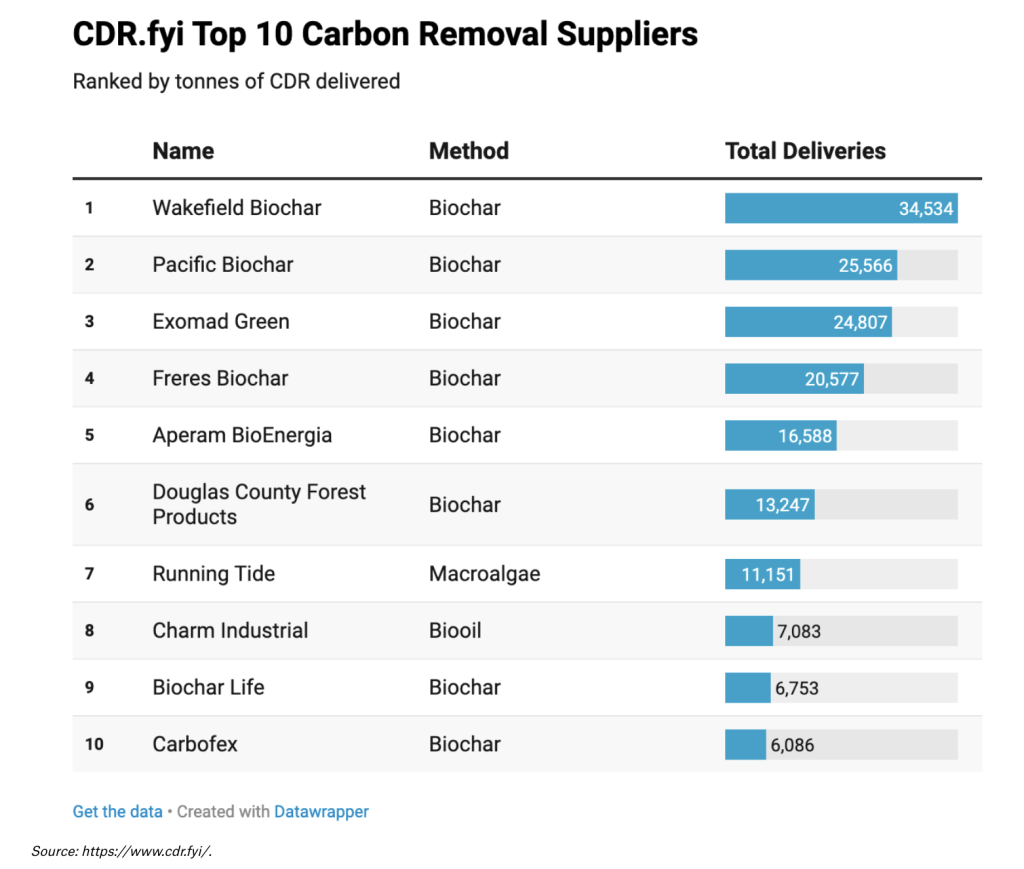

The same is true of biochar carbon removal, which involves pyrolysising residual biomass and applying the resultant ‘biochar’ to soils or durable materials like cement or tar. It is by far the leading approach in the burgeoning carbon removal market, boasting eight of the top ten leading companies by delivered carbon removals last year, according to market tracker CDR.fyi. “In theory, [biochar] is a really positive thing, but at the moment – as with all the soils-based approaches – we don’t have great ways of assessing the whole systems-level impact,” says Buma.

Thankfully, however, the vast majority of the existing investments in the carbon markets are in solutions with high scientific credibility: 70% of nature-based credits that come from American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve, Gold Standard and Verra are for projects in the four leading forest-based activities.

“It is not a matter of either nature-based solutions or technology-based carbon capture approaches, we are going to need every tool in the box – according to the IPCC, we will need 20–30% of the overall climate solution to come from natural systems,” says Doria Gordon, lead senior scientist at EDF. “The technology-based approaches will take some time to develop, but in the meantime, we really need to scale the natural systems to get where we need to be by 2030.”