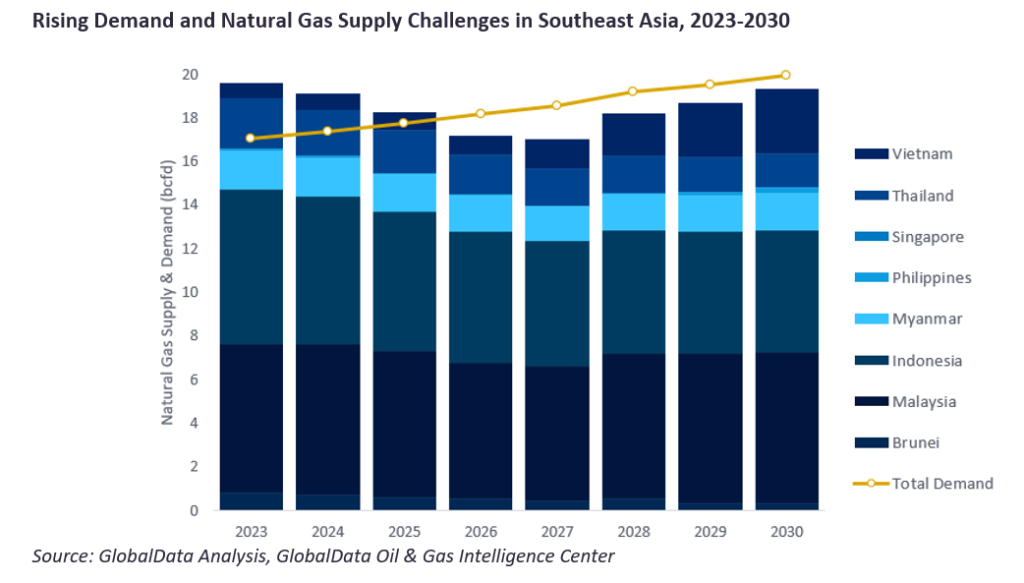

As gas demand soars and supply potentially fails to keep pace - what does this mean for energy security in Southeast Asia?

The natural gas market in the region is at a critical juncture, driven by rapid industrial growth and urbanisation. The shift in energy demand amid heavy investment in LNG [liquefied natural gas] infrastructure is overshadowed by geopolitical tensions on its future energy supply. The “Southeast Asia Natural Gas and LNG Outlook 2024” is a report that provides an in-depth analysis of such key trends - a must-read for all investors, policymakers and industry leaders interested in developments within the dynamics of the region’s energy market.

As the region continues to grow, so does the demand for natural gas. Energy demand in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand has been driven by industrialisation and urbanisation. Natural gas has emerged as a major fuel for electricity generation in the region, and demand is expected to rise steadily until at least 2030.

The region, though rich in natural gas, may suffer a shortage from 2026 according to forecast data. With more countries such as Indonesia driving up domestic consumption to service their own energy requirements, reliance on imports could surge within the region. Without major new discoveries or increases in production, Southeast Asia will shift from self-sufficiency to become a net importer of LNG, casting uncertainty over not just regional, but global markets too.

Infrastructure developments

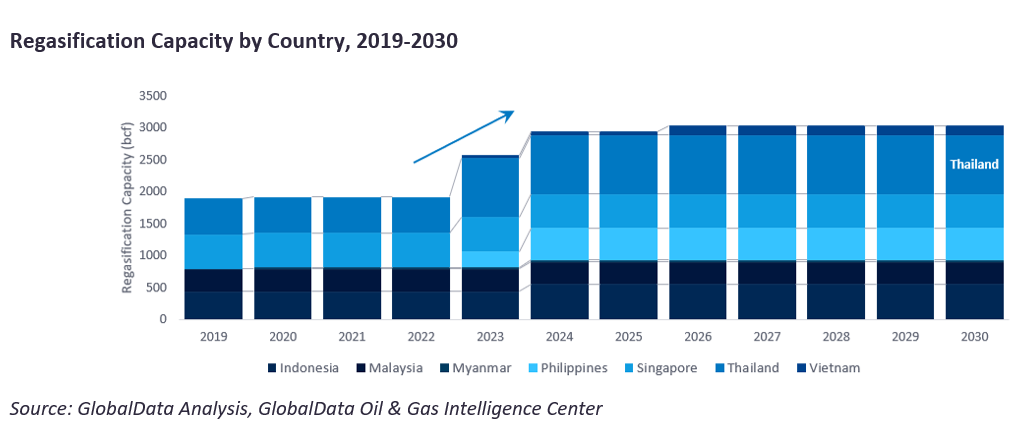

To meet increasing energy demand within the region, it requires large-scale investments in gas pipelines and LNG infrastructure. Projects considered key in the region include the Trans Oriental Gas Project connecting Malaysia and China, allowing for better cross-border energy connectivity. Other new pipelines will link Vietnam and Thailand to bolster energy supplies and regional energy security.

Thailand is emerging as a regional hub for LNG regasification, with capacity forecast to reach 925.3bcf by 2030. Regasification terminals provide a country not only with an opportunity to import LNG, but to also convert it into its gaseous form and distribute it with the help of its domestic energy grid. In the face of increased demand for LNG, especially for countries such as Vietnam, regasification terminals will be of great importance for a continuous uninterrupted supply of energy.

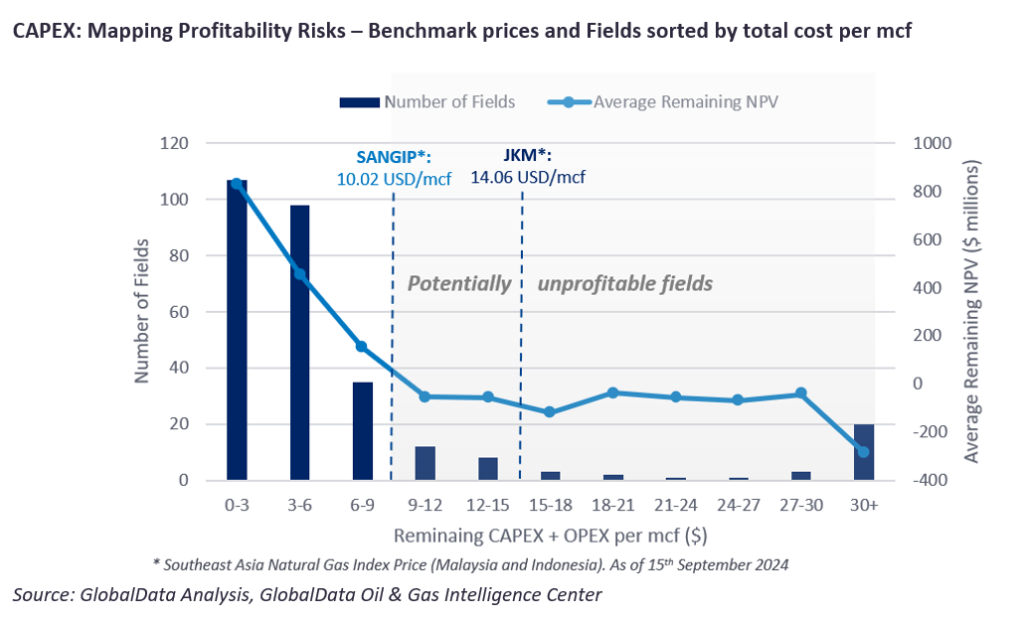

The CAPEX expenditure histogram shows cost variations, showcasing both profitable fields and high-risk projects. Most fields fall into the expenditure category of $0 to $6 per mcf, given their potential to provide major profits. These fields represent $1.2 billion of combined remaining NPV [net present value] and are therefore crucial from a future supply perspective.

The histogram in also points out more riskier fields with expenditures over $12 per mcf [thousand cubic feet], making them less profitable. Investors will need to understand where these high-cost fields are located to assess the long-term financial viability of projects. The CAPEX histogram helps decision-makers to lock resources onto cost-effective fields while being aware of less financially viable projects and investments.

Geopolitical risks: weathering stormy waters

The South China Sea is a geopolitical flashpoint, with shipping lanes dominated by China at the crossroads of supplies towards not only Southeast Asia, but global energy needs too. Around a quarter of LNG traded in the world passes through these waters, and any incident here could pose a danger to global markets.

The influence of China extends beyond territorial claims. With the Belt and Road Initiative, China has become a major investor in building energy infrastructure in the region. While the added development is welcome, such investment also provokes dependencies that may narrow Southeast Asia’s options in the long term. For investors, understanding these dynamics is crucial to mitigating risk and clearly seeing opportunities.

Energy transition: bridging the gap

While natural gas will continue to play a central role in Southeast Asia’s energy transition strategy, it will also accelerate its energy transition. With governments pressing for cleaner fuel sources, natural gas is considered the main transitional fuel. It burns much more cleanly compared to coal, which has dominated the region as the largest fuel source for years. Its increasing use for power generation in the region is also targeted as part of efforts to be less carbon-dependent. By 2030, gas is expected to surpass coal as the largest source of power in Southeast Asia.

It also speaks to increasing interest in carbon capture, utilisation and storage project development, with 21 announcements in the region to date, led predominantly by Indonesia and Malaysia. This signals the commitment and efforts of Southeast Asia to decrease its carbon emissions while continuing to exploit its natural gas infrastructure. Whilst none is yet operational, they are an important first step in the region’s journey toward a greener future.

Conclusion: a market in transition

The Southeast Asia Natural Gas and LNG Market Outlook 2024 provides a multi-varied look into the energy landscape of the region, against a backdrop of demand growth, expanding infrastructure and not least, geopolitical challenges. The CAPEX expenditure histogram enables readers to know which are the profitable fields and which may present financial risks. Investors, policymakers and industry operators need to understand these dynamics, as proper, timely, informed decision-making has increased importance in a market that constantly changes.

Southeast Asia’s natural gas future is fraught with both opportunity and challenge. Amidst a balancing act between economic growth on one hand and energy security and sustainability concerns on the other, regional decisions made today set the energy landscape for many years to come. This report equips readers with the critical data and insights needed to make informed, strategic decisions in the region’s gas market.