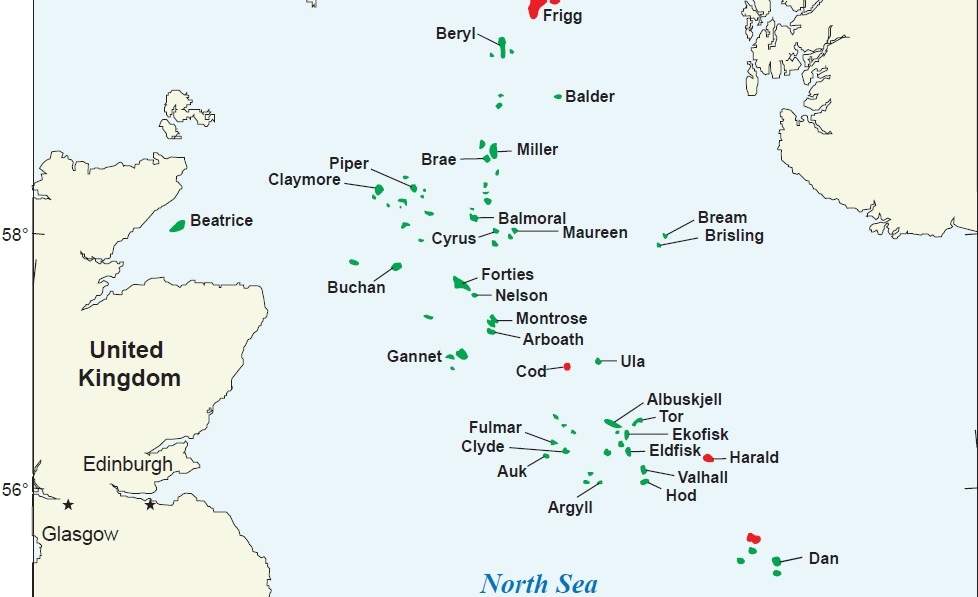

Piper Alpha was the biggest single oil and gas rig in Britain, producing 300,000 barrels of crude a day. Oil was discovered in the Piper field in 1973, and Alpha began production by 1976 before being expanded in 1983 to produce gas. At this point, the platform was responsible for 10% of all the oil and gas produced in the UK.

On 6 July 1988, a breakdown of communication during a shift change meant workers were unaware that a key piece of pipework had been temporarily sealed and there was no safety valve. Gas leaked out and ignited, spreading quickly through the platform as the firewalls, only designed to cope with oil fires, failed. Of the 228 workers on board Piper Alpha and on nearby servicing vessels that day, 168 died as it was completely destroyed. It took three weeks for Red Adair to get the flames under control, and cost the Lloyd’s insurance market more than £1bn.

The Piper Alpha disaster displayed the immense danger of gas leaks, but has the problem been eliminated? No – every year tens of hydrocarbon releases are recorded on rigs off the coast of Britain. In 2016, 73 major, minor and significant releases were reported to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). With the anniversary of the disaster approaching, the HSE has written to offshore oil and gas companies currently operating in the North Sea about their hydrocarbon releases to try to crack down on the problem once and for all.

“Hydrocarbon releases are one of the key performance indicators in the industry and although the minors and to a certain extent the significants have been falling in number, the majors – which is what Piper Alpha was and which is the main thing that we’re trying to prevent – the majors are not showing any discernible reduction,” explains HSE Energy Division offshore operations manager Howard Harte. “So we wrote out really to alert the industry as to what these issues are, but to then let them do a self-audit of themselves, so they can then understand better if they are managing these risks appropriately.”

Major leaks, major problem

Hydrocarbon leaks are classified as minor, major or significant, based not only on the amount leaked but also by the platform’s production capacity, and all must be reported to the HSE. In 2016, these accounted for over a quarter of dangerous occurrences in the offshore workplace.

“Major hazard management is not an easy task and it does require this high degree of awareness of what’s happening in each company,” says Harte. “It’s a difficult problem to resolve and we’ve tried all sorts of different programmes ourselves as the regulator, key programmes, but we’ve realised that we need to do something a little bit differently to deal with this particular issue.”

While the data for minor and significant gas leaks has shown consistent reductions, the same cannot be said for major leaks. In 2008, for example, there were 52 significant releases, 93 minor leaks and two major. By 2016, these had been reduced to 35 significant, 55 minor and one major. Although there is some fluctuation year on year, there is a steady trend of reduction for minor and significant leaks, unlike major leaks.

One key challenge is that major incidents tend to be due to human error, as opposed to a hardware malfunction.

“The root cause of leaks is either down to a hardware failure or an operational or software failure,” says Harte. “The root causes of the minors tend to be more associated with hardware failures than operational failures, whereas the major releases tend to be focused more around these operational failings.”

“So with operational failings I mean things like competence, up-to-date procedures, and all the documentation in place. It’s these sorts of people-focused, soft-debate activities that tend to be the lead cause of the majors, whilst minors tend to be more about hardware failings. So a bit of pipe corroding more quickly than people thought and it’s led to a release.”

Improving offshore safety through sharing

Improving safety on offshore rigs by minimising hydrocarbon leaks is not an easy task. HSE has identified leadership and a lack of sharing best practices as potential reasons for the latency of improvements. Many oil and gas companies remain secretive about their processes and practices in an effort to protect their reputations and share prices; however, this makes it much harder to learn from one another.

“That’s why Chris [Flint, HSE director of energy division] wrote out to all the production duty holders,” says Harte. “That’s why we’re actually going to then try to pull together all the findings and actually encourage – I think what doesn’t happen sufficiently is there’s not enough open sharing and learning from these incidents so we’re hoping that companies will do a lot more of that.”

The companies approached have until 20 July to complete a self-audit and submit it to the HSE. It will then be able to evaluate the findings and provide informed advice for the future.

“What we’re trying to encourage is a robust process safety leadership and demonstrate that it requires highly visible leadership, commitment and responsibility and, in particular, a high level of awareness of process hazards and their potential,” says Harte. “So the leadership bit is all about getting involved, taking responsibility, having appropriate assurance audits and review mechanisms in place. And it’s also about ensuring that the workforce is fully involved in the process too.”

Despite the challenges hydrocarbon leaks provide, the safety of offshore operations continues to improve. As the industry adapts and changes to accommodate the market and key trends, best practices will too ensuring the future of offshore operations in the North Sea look bright.

“There’s only half the total oil reserves being exploited, there’s a really positive set of conditions around now,” says Harte. “It’s going to be different, there’s going to be a lot more robotics and digitisation of activities but for me I see it as a very positive place to be.”