The days of cheap and easy-to-drill oil are over. Now comes the hard work of finding and producing oil from more challenging environments.

Those were the words of ExxonMobil in 2005 and seven years later, oil and gas operators and consultants are becoming increasingly aware of the rate in which conventional wells are drying out.

According to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas, many countries have passed their peak rate of oil production, suggesting the world peak of production is now imminent.

As a result, oil and gas firms are looking to squeeze every last drop of reserves from the nooks and crannies of the ocean, in hard-to-reach, ultra deep places.

In March 2012, the UK Government assigned a £3bn new field allowance for large and deep fields to open up in the west of Shetland, an incentive many explorers will find hard to resist.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataOf course, there are huge environmental and safety risks to drilling in deep waters – as witnessed in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster – but as industry experts agree, we can’t afford to ignore the last remaining oil and gas reserves which have the potential to boost the economy during these tough economic times.

West Shetland drilling potential

In his annual budget speech in March 2012, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne pledged his support to oil and gas firms by introducing a £3bn new-field allowance for large and deep fields to open up west of Shetland.

This area, located in the North Sea, is estimated to hold about 20% of the UK’s remaining oil and gas reserves, or 3.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent.

The industry reacted well to this news, including Deloitte head of tax Derek Henderson, who said: “The measures show willingness of government to work with industry to create an environment in which the maximum economic recovery of hydrocarbons from the UK North Sea can be achieved in the years to come.”

Oil & Gas UK also welcomed the chancellor’s announcements. Chief executive, Malcolm Webb, said at the time: “The changes announced are the result of over a year of constructive, collaborative work and reflect the Treasury’s proper and considered approach to the industry’s proposals.”

BP has since jumped at the chance to explore to the west of Shetland and announced just one day after the budget speech that it has been given consent to a drill a deep-water well in the area.

The North Uist well lies about 125km to the north-west of the islands, at a depth of nearly 1,300m, a stark contrast to its shallower, 140m-deep Clair Ridge project which is closer to the coast line.

Chevron has also expressed interest in drilling underdeveloped areas in the Atlantic Margin, following its discovery of oil in the 1,100m-deep Rosebank exploration well in the Faroe-Shetland Channel in 2004.

The company has called upon contractors to supply a custom-built, harsh-environment, deep-water drill, which it says could be delivered in 2014 at the earliest.

It seems oil and gas firms are seeking harder-to-reach wells and easy oil in shallower waters, but it is the deepest wells which are said to be ones with greatest risk.

Retrieving oil under extreme pressures

Oil and gas which lies miles below the ocean floor could perhaps provide the UK with the best shot at energy independence.

But, compared with conventional offshore drilling methods, deepwater presents unique dangers related to higher pressures and extreme temperatures.

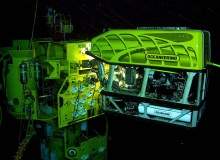

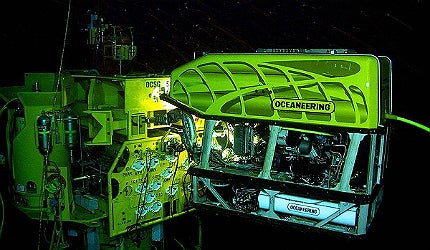

A.T Kearney partner in the energy and process industries practice Jim Pearce says: “The challenges that you face in deepwater are largely around the fact that you are typically operating in water depths of 1,500 metres and beyond with thousands of pounds of pressure. You need ROVs [remotely operated underwater vehicles] which are unmanned submarines to help you.”

“You also get the challenge that the water is deep, but the wells are also deep, so often what you get is HP-HT [high pressure – high temperature]. You may be very cold at the bottom of the sea [where the temperatures are just above freezing], but the deeper you get, the higher the pressure and the temperature. You can reach up to 35,000 psi in deep holes and temperatures of [more than] 450 Fahrenheit.”

The pressure of the well is controlled by ensuring that the pressure of the drilling fluid in the well bore is sufficient to oppose the pressure from the oil, gas and water in the reservoir. This prevents fluids from the reservoir from entering the well.

But, if the formation pressure is greater than the bottom hole pressure oil and gas would enter the wellbore, which could lead to a blowout if uncontrolled, BP’s former group CEO Dr Tony Hayward told the UK Parliament for its report on the implications of the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill.

Another challenge faced by deepwater operators is manipulating the extra long riser pipe which is needed to connect the wellhead to the rig.

Pearce explains: “If you imagine you have got this thick hole at the bottom of the seafloor, as the waves moves the vessel you’ve got to try and keep this thing right above the hole even when the tide is moving it. So what you need is dynamic positioning systems which link to satellites to try and keep the vessels where you want them.”

Oil and gas firms also face high costs when drilling in deep waters, due to the need for technologies that can work in extreme environments and the fact that there is a lifting cost per barrel. It can take months to drill a deepwater well and they cost, on average, $100m.

But Pearce believes the drive towards deep water drilling will have positive implications for the economy and the energy industry as a whole.

Pearce says: “With these complex projects in deep water, the development has a lifting cost per barrel which will be more than in a land well or easy-to-drill area. Therefore, by definition, this does make certain alternative energies more competitive against oil and gas in deep water.”

Environmental threats from squeezing “every last drop”

The immediate extension of the field allowance regime to deep fields west of Shetland, it is argued, promise an allowance for new investment in existing fields and infrastructure.

These measurements should also result in additional investment of more than £10bn and the production of millions of barrels of the UK’s oil and gas, according to trade association Oil and Gas UK.

But, the UK has faced strong criticism from environmental groups for allowing exploration in the area.

Dr Dan Barlow, head of policy for WWF Scotland, argues: “Developing a zero carbon economy requires a strategy that focuses on ending our addiction to oil and gas, not seeking to squeeze every last drop from beneath the seabed.

“In addition pursuing North Sea oil exploration in ever more difficult and sensitive areas is just not worth the environmental risk, the Shell spill from Gannet Alpha last year [2011] showed that even in easy waters, a long experienced operator can make a total mess of dealing with an oil leak. Any significant oil spill to the west of Shetland area could present a major threat to fishing, tourism and wildlife.”

Since the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the UK Oil Spill Prevention and Response Advisory Group (OSPRAG), has designed a cap capable of stopping a well flows of up to 75,000 barrels a day in water depths of 1,670m.

But the environmental group Greenpeace has said there are wells where the cap is unlikely to be effective in the event of a major blow-out.

Barlow believes that the power industry needs a proper plan to wean us off our oil dependency, saying: “By making the most of our fantastic renewables potential and using energy much more efficiently, we are well placed to make a transition to a clean and secure energy supply, create thousands of green jobs and protect households from rising bills.”

While green projects are developing, however, it could be argued that we need to make the most of existing resources while we make the transition into becoming 100% renewable.

There are risks to drilling in deep water, but these risks can be mitigated, as Pearce explains: “No one in the industry would want to take unnecessary risks, whether myself, an operator or a service company, and clearly we should do everything we can to mitigate those.”

“The UK has received some praise for its stringent assessment of environmental impacts of the Deepwater Horizon incident, as well as its safety system which works to assess risk and follows best practice,” Pearce adds.

“I think that we shouldn’t over-rely on oil and gas in deepwater because of the technical risk, but as the costs are more, other sources of energy will also become competitive. That’s not saying deepwater is at the exclusion of others sources and of course we should investigate them.”