Deepwater oil and gas operations are continuing to grow in number as companies around the world seek large, dependable reserves. Of the 2.7 trillion barrels of remaining recoverable conventional oil estimated by the International Energy Agency, approximately half is located offshore. Of this, 25% – or 340 billion barrels – is made up of deepwater reserves.

Companies such as Shell have identified deepwater reserves as key areas of development in coming years. However, in the US port facilities are struggling to cope with these monster rigs and the specific challenges they create.

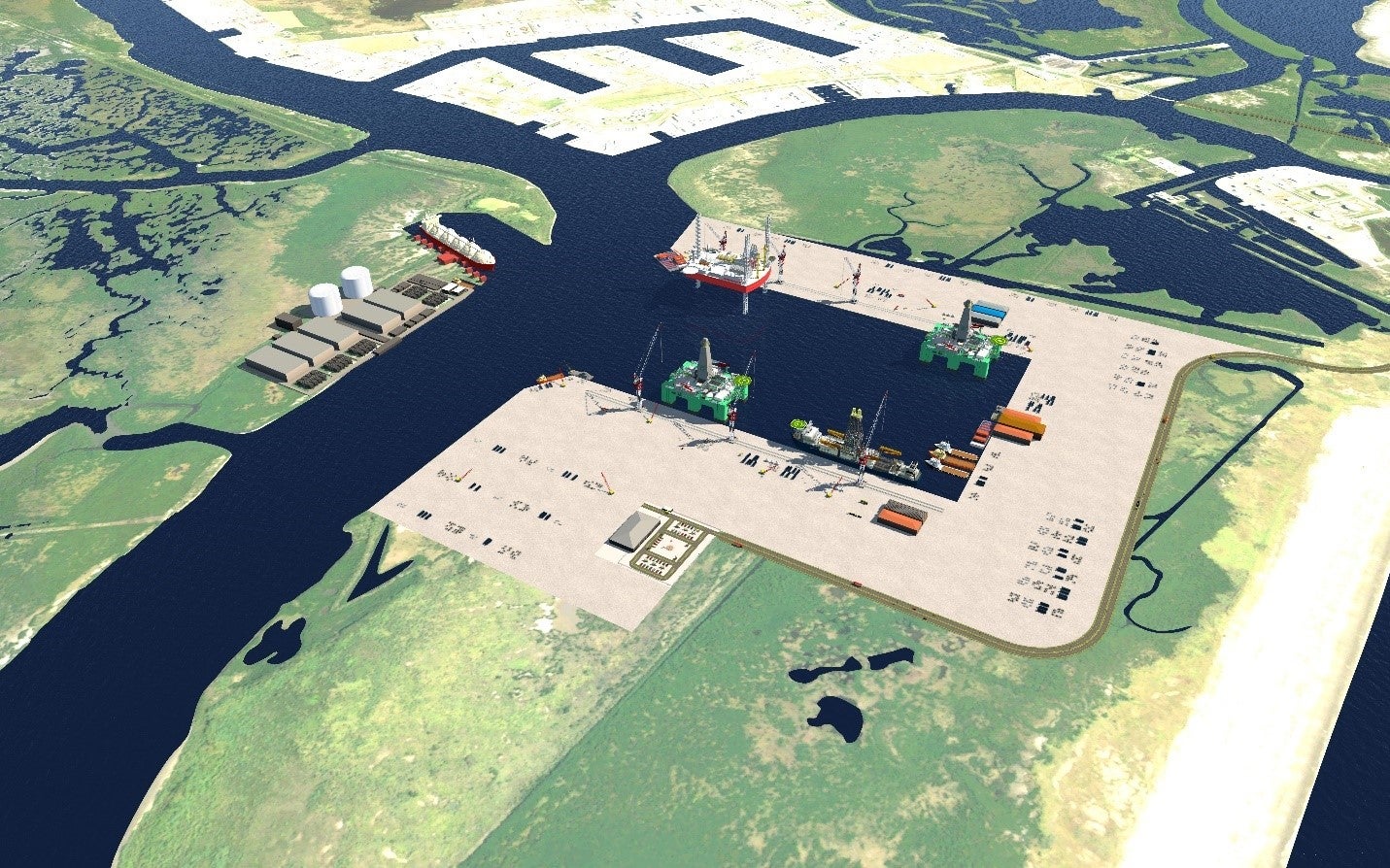

The Greater Lafourche Port Commission (GLPC) announced in September that it had signed a lease for 900 acres of land on which to construct a new deepwater port facility. Located at Port Fourchon, Louisiana, the facility will be equipped for rig repair and refurbishment.

“We’re going to go to -50ft, so a 50ft draft, and we’re going to do the initial phase of dredging and development of a deepwater rig repair and refurbishment facility in order to service currently the rigs that are unable to be serviced in the US Gulf of Mexico as far as repair and refurbishment,” says GLPC executive director Chett Chiasson.

Rigs require repair and refurbishment on a regular basis to meet health and safety standards. They are battered by winds and water, which wears down paint and metal over time, meaning they have to return to shore to be evaluated and any potential problems fixed.

Port Fourchon’s deepwater facility will be able to offer these services to the growing number of deepwater rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. It has now submitted a draft feasibility report and draft environmental impact statement to the US Army Corps of Engineers, and hopes to submit the final documents by January 2019.

Growing deepwater activity

Currently, deepwater projects account for just 7% of oil production globally, but this is set to rise to 11% by 2040. Much of this expansion will take place in the Gulf of Mexico, where operations are already underway.

Deepwater rigs are those where drilling takes place in water depths of greater than 125m, while ultra-deepwater operations begin at 1,500m. Technological developments of dynamic positioning equipment, rigs and drilling units have made it possible to reach such deposits in recent years, and there are now over 3,000 deepwater rigs in the Gulf of Mexico alone.

“There’s a large number of drill ships and some semi-submersibles, floating rigs and more that are in the Gulf and from our discussion with the rig owners, a new facility in the US is desperately needed,” says Chiasson.

The swift growth in deepwater offshore drilling rigs has not been paralleled with a growth of onshore support facilities. While increases have slowed in recent years following drops in the oil price and increased competition from onshore sources, the demand for port facilities capable of handling deepwater rigs remains.

“It is a challenge because there’s not enough capacity in the United States to handle all of the repair and refurbishment market for the rigs that are actually sitting in the Gulf of Mexico,” says Chiasson. “So what we’re trying to do with our new facility that we’re embarking on is be able to increase the US’s capacity to service those deepwater drilling rigs and drill ships.”

The Fourchon Port facility, which will be known as Fourchon Island, will not be the first of its kind, but certainly they are not common globally. At present, the vast majority of deepwater operations are located in just four countries: Brazil, the US, Angola and Norway. Brazil and the US together account for as much as 90% of ultra-deepwater production.

Louisiana is a key area for continued growth for the US oil and gas sector, in particular deepwater production. Currently 20% of the US’s oil and gas is pumped from or transported through the Louisiana wetlands.

Dredging and its effects on Louisiana’s wetlands

In order to facilitate the deepwater rigs, the GLPC will need to dredge a large draft leading into Port Fourchon. It is hoping to begin this work in 2020 and is currently in conversation with tenants of the port capable of such work.

“Our goal is to use every speck of sand we dredge beneficially, and in the first cut of this deepening we’re going to generate about 20 million cubic yards of material,” explains Chiasson. “We need 12 million for mitigation, for the impacts to the marsh as well as for the development of the facility. So that’s going to leave about 8 million cubic yards of material available for beneficial use. And the plan currently is to utilise that material beneficially to do some positive work in rebuilding even more marsh than we need to for our mandated mitigation.

As a state, Louisiana requires mitigation works to take place to protect its fast receding shore line. Between 1932 and 2016, the state’s coastal parishes lost 5,197km2 (2,006 square miles) of land.

“We live in an area that’s sediment starved, we’re in between the Mississippi River and the Atchafalaya River and we have no sediment that rebuilds the land naturally,” explains Chiasson. “So over the years, since the Mississippi River was levied in in the 1930s, we’ve been sediment starved and subsiding. Our land is eroding away. It’s no secret that Louisiana has one of the most rapidly eroding coast lines in the world and we have a coastal master plan in the state of Louisiana that does coastal protection and restoration projects. This project that we’re embarking on would go a long way with all that extra material to meet the projects that are included in the state’s master plan for restoration and protection.”

Previously, the GLPC constructed approximately 1,000 acres of wetlands as part of its environmental mitigation programme. It has elevated and developed a further 1,000 acres it says would otherwise have been lost to coastal land loss, and constructed the first maritime forest ridge restoration project in Louisiana.

Mitigation projects are working, and the rate of loss has slowed since the 1970s. The most recent data from 2016 showed that, based on satellite imagery, the land area estimate was approximately 16 square miles greater than was estimated in 2010.

Given the delicate nature of the wetlands and surrounding ecosystem, it is paramount that GLPC’s environmental impact statement, currently awaiting approval, is exhaustive. It will be based on over two years’ worth of environmental, economic and engineering studies evaluating the dredging of the slip and the construction of the land needed for Fourchon Island.

“It’s really an excellent environmental project, not just an economic project,” says Chiasson. “So that’s really what we’re excited about, that we can do things that are necessary to rebuild at the same time providing more jobs and economic development for our communities.”

The plans for the new port facility have been welcomed by the local community around Port Fourchon. The area has a long history as part of the oil and gas industry, and the port is already a key employer.

“The local community is very excited about the potential of this project, and the potential of anywhere from 1,000 to 1,300 jobs that could be created,” says Chiasson. “We’ve been very lucky to have a very supportive community that gets excited about these big projects.”

As demand for oil and gas continues to grow, companies are increasingly looking to deeper reserves. But for the rigs to be successful and remain safe, onshore port facilities much catch up.