For the first time in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) 45-year history, this year’s ASEAN Regional Forum in Cambodia failed to produce a joint communiqué to the world.

Despite a wide range of disputes in the past, this unified statement has always provided a representation of the member countries’ commitment to peace and cooperation, moving towards the potential introduction of a formal economic community in the next few years.

For the first time in nearly half a century, the ASEAN states were unable to reach a consensus on this year’s joint statement. The sticking point is a wide-ranging dispute between a number of south-east Asian nations and close neighbour China on sovereignty over various areas of the South China Sea.

Although the dispute has broad significance concerning the geopolitical stability of the surrounding region, the presence of potentially massive oil and gas reserves in many of the disputed zones means offshore exploration is intimately connected to the wider crisis.

South China Sea dispute: key players

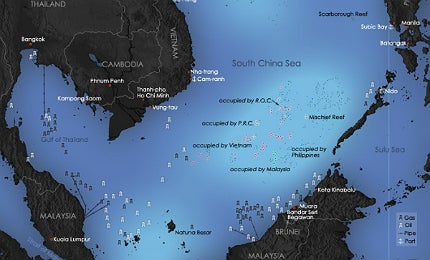

The root of the disagreement lies in a complex web of international maritime law and national territorial claims. China, the region’s undisputed powerhouse, continues to lay claim to more than three-quarters of the South China Sea, demarcated by its so-called ‘nine-dotted line’, which extends from China’s south coast almost to the northern shore of Malaysia.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataChina’s aggressive claim has provoked outrage from Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines and other countries, as it infringes upon their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) as set down by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), giving countries the right to exploit marine resources up to 200 nautical miles out from their coastlines. The UNCLOS treaty has been signed and ratified by the European Union and 162 states, including China.

Particular tension has sprung up in three specific areas, over all of which China claims some level of sovereignty. China is disputing sovereignty over the Paracel Islands with Vietnam and Taiwan; the Scarborough Shoal with the Philippines; and parts of the Spratly Islands with Malaysia and the Philippines.

These archipelagos serve little strategic or demographic purpose, but the prospect of exploring potentially oil-rich offshore blocks provides a lucrative economic background to these tensions.

China looms large at ASEAN conference

The South China Sea controversy, and China’s powerful influence over the Asia Pacific region, cast a shadow across ASEAN’s Regional Forum in July.

China’s position at the summit was to keep the territorial disputes out of the discussions, with many diplomats claiming that it applied severe pressure on host nation Cambodia, which is economically reliant on Chinese investment, to keep the South China Sea off the table.

As a result, the Regional Forum was an uncharacteristically tense affair, as suspicions flew back and forth that the issue was being locked out of discussions by Cambodia, with China pulling the strings.

Carlyle Thayer, Australian Defence Force Academy emeritus professor, told Reuters that these suspicions have opened an unprecedented rift in regional relations. "This is the first major breach of the dyke of regional autonomy," he said. "China has now reached into ASEAN’s inner sanctum and played on intra-ASEAN divisions."

It certainly makes sense that China favours, as it has stated, internal discussions with ASEAN countries over a multilateral approach that would lean towards the international UNCLOS treaty, which would generally favour the claims of the smaller south-east Asian countries.

As such, the country has been arguing for separate bilateral talks to leverage its influence on the region rather than expanding the argument to a more globally inclusive scale. As the following South China Sea flare-ups show, however, there seems to be little chance of reconciliation at the moment, as all parties argue their case with increasingly aggressive gestures.

Vietnam, China and the contested Block 128

The Paracel Islands fall on the disputed border between Vietnam and China’s EEZs, although China’s nine-dotted line claim extends far beyond them and towards the Vietnamese coastline itself.

The Vietnamese Government has asserted its right to the disputed offshore regions by exploring blocks 127 and 128, in collaboration with Indian national oil and gas corporation ONGC, thus dragging the south Asian country into the politically charged South China Sea contest.

ONGC has since relinquished its rights to Block 127 due to a lack of hydrocarbon discoveries, and was on the brink of doing the same with Block 128 when PetroVietnam offered the company favourable terms (and new exploration data) earlier this month to continue to explore the block.

"They [PetroVietnam] told us to put two more years in the blocks and gave us additional data to improve the prospectivity in the block," said an anonymous executive of ONGC’s overseas division OVL. "We are studying the data. The decision has been good for us as there is no additional responsibility. The two-year period has started and OVL will continue in the block."

CNOOC launches competing tender

However, China has been equally assertive in the regions surrounding the Paracels, as its own state-owned oil and gas company China Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) put nine offshore blocks in the region up for global bids.

Related project

PetroVietnam’s Hac Long Field, Vietnam

River basins across the world are rich in oil and gas reserves. The Red River basin in the northern region of Vietnam also has large oil and gas reserves.

The areas offered for bids include Block 128, which OVL is already exploring. This aggressive move has incited widespread protests in Vietnam and puts strong political connotations on the contract tendering process.

CNOOC has stated that the tender is progressing well, with even some US oil companies expressing an interest, although many analysts believe that major corporations are unlikely to commit to the region until the disputes have been resolved and the territorial picture becomes clearer.

"Some of the blocks are known to be in the disputed waters," IHS energy consultant Huang Xinhua told Reuters. "And since PetroVietnam has told companies not to take part, few would have the appetite for that kind of risk."

Whether Vietnam’s contract extension with ONGC is based on promising data on Block 128’s oil reserves or simply a holding pattern to reinforce its claim to the area won’t be known until further exploration is conducted. But it’s clear that both countries are refusing to back down, even as the diplomatic standoff becomes more and more tense, with China’s Central Military Commission recently authorising the establishment of a military garrison in Sansha City in the Paracels, which serves as the administrative centre for China’s claims to the South China Sea, including the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal.

The Spratly Islands dispute

Related project

Lishui Natural Gas Field, China

Lishui 36-1 is a natural gas field located 150km away from the city of Wenzhou in the East China Sea.

The Spratly Islands, an area of more than 750 reefs, atolls and islands, lies just north of Malaysia and west of the Philippines, which, along with Brunei, Taiwan, Vietnam and Indonesia, have laid claim to parts of the archipelago. The potential hydrocarbon reserves in the region have been estimated at around 225 billion barrels of oil equivalent, including around 900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, three times the proven natural gas reserves of all the competing countries combined, China included.

With the potential for reserves on that scale, it’s perhaps unsurprising that China, and its ASEAN rivals, are desperate to develop the Spratly offshore region to reduce energy dependence and invest in a sure-fire economic winner. In legal terms, UN-sanctioned international law would once again favour the nearby ASEAN nations to varying degrees, while China is again relying on historical claims and its nine-dotted line.

The most high-profile dispute currently simmering in the Spratlys is between the Philippines and China. The Filipino Government, which counts the US as a strong military ally (joint military exercises involving the two countries were carried out in the South China Sea in April), has pushed its claim to eight islands in the region, as well as the Scarborough Shoal, which the country considers to be essentially part of the same claim.

In March, the Philippines invited bids for oil exploration contracts in three blocks in the region, drawing China’s scrutiny.

"Without permission from the Chinese Government, oil exploration activities by any country or any company in waters under China’s jurisdiction are illegal," said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin.

Filipino Energy Undersecretary James Layug responded: "All reserves in that area belong to the Philippines. We will only offer areas within our exclusive economic zone. These are all beside our existing service contracts so there is no doubt that these areas belong to the Philippines."

With resources that could ensure energy security and provide a trickle-down economic benefit for decades to come, ASEAN, China and the whole Asia Pacific region seems to be caught in a multipronged Mexican stand-off, with no party willing to stand down and give up their territorial and economic rights.

This could be the most significant test of the ASEAN countries’ resolve and diplomacy since the international organisation was formed in 1967; the negotiations that take place in the months ahead could define the geopolitical and economic outlook for the entire region for years to come.